Host for the Swarm

When you’ve finished your soup, take my boots. My hat and cloak are yours also. I must be rid of everything, especially my words. They’ve cost me so much. Not by taking from me, but in the proliferation of myself into many small parts. I began as a holy fool in Russia, wandering from place to place, receiving alms in return for prophecies and parables, as was the custom. But the stories replaced me grain by grain, as silica from chalk becomes flint. I’ve wandered too long now, I’m quite out of sync. Stay, friend, stay, I’ll help you spend your time.

Once I was the police chief of Odesa during its heyday as the centre for grain export. My father rebelled against the Tsar when I was a boy. After twelve years in the hellish mines of Nerchinsk, he was exiled to settlement and there he died. Last week I arrested the governor of Odesa and am awaiting orders from the Tsar’s secret police. But – cursed timing! – my father isn’t dead. I have been sent, by way of the Italian who runs the lazaretto and opera house, a secret packet announcing my father’s rebellion from Siberia.

What could I do but retreat from my doom? I became a woman who defended a barricade in the streets of Paris during a minor French revolution. Disillusioned with the wealthy men that replaced the other men of wealth, I dealt with defeat by joining the enemy. Until last week my husband was the governor of Odesa. I suspect the Tsar of personally issuing the arrest order and when he attends a party at my seaside palace I’m going to cut his throat.

Ah, yes! You see the problem, too. The police chief pulled me back into his tale. For fifty years I tried to evade him, weaving in and out of modest local yarns that should have escaped his notice. What I could tell you about the gangland kings in old town Moldavanka! And the travellers and fugitives in the lazaretto, where disease in Constantinople pays for divas to enchant our own opera zealots.

What a goose chase I led the police chief on, dropping down wells and escaping at my leisure through the catacombs and tunnels that undermine the city. Eventually he himself gave me the chance to see the world. That was when I became a student who fled Odesa after a pogrom at the turn of the twentieth century. I sought refuge with my cousin, a master tailor who owns a small sweatshop in east London. Yet this too will end in misery. I’m going to betray my cousin by enticing his eldest son into striking against the sweatshop owners. Later, in shame, the poor boy will join up, only to suffocate to death in the mud of the Somme.

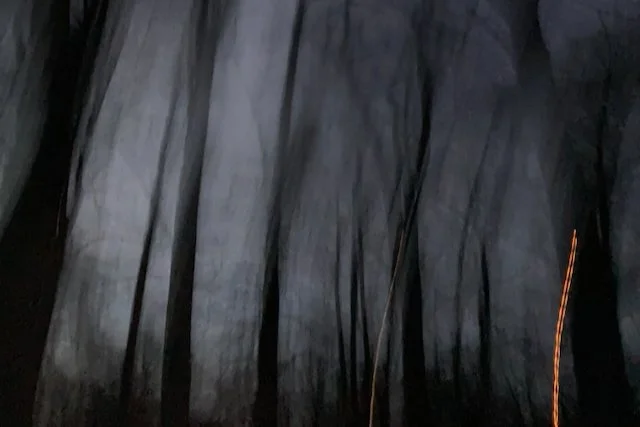

Yes, the allure of the underland is very strong.

With true faith in my heart and eager to make amends, I became a girl in the Lake District who’s hellbent on reforming the family bobbin mill. Just after I was born, my father surrendered the mill to my uncle, then disappeared amid rumours of his association with a known highwayman. This morning my uncle and his thugs arrived at my grandmother’s cottage to take me to an asylum masquerading as a school for wayward young ladies.

I deserved it, I know.

You’re quite right, friend. Why should a storyteller emerge from her story unscathed? I escaped across the moors, chased by starved hounds, and fell in with a gang of highwaymen myself. At this point I indeed lost my way. I’ve no choice but to become the woman who tricks this runaway girl into helping kidnap a banker’s daughter in Manchester–

Oh, my people have caused so much trouble!

No, I won’t have a drink, but thank you. If only it were as simple as obliterating myself.

Soup? No, I don’t eat either. Here, put on my hat until your broth warms you. It’s a good Russian hat. Oh yes, very becoming. A foolish storyteller needs a good hat. There are times when one needs to feel contained.

I crossed the Urals many times. I even marched with General Cuckoo’s army for a while. We prisoners in Siberia took the cuckoo’s spring call as our herald to escape from the camps. In our thousands we made our way through the forests back to European Russia. What we did in the villages and to each other along the way… I’ll never forgive myself. All in the name of survival, friend, you know how it is. I knew men flogged so often their shoulder blades, like ivory carvings, were permanently uncovered by skin, as if they were about to sprout wings, for God’s sake. If you’d seen what I saw, you’d have done what I did.

What business brings you here? You’re searching for something, I see your restlessness. Perhaps I can help. I have modern stories, too, if that’s more your taste? They do have a similar feel, however. I admit I always go for my own jugular. It’s what the audience wants.

It’s possible that other fools have found a better way but I haven’t met them myself.

You can be a man who accidentally starts a cult. He’s said to resemble Nansen, the Norwegian explorer, for the intensity of his jackdaw eyes.

Not for you? Quite right. I confess that he becomes trapped by his own followers and terrible consequences ensue. Perhaps you want to be a woman whose boyfriend has died during an Everest attempt. His body remains there, preserved in ice.

Well, in a manner of speaking he is immortal. He may be dug up in some distant age when the world is unrecognisable to us.

Very well. Then how about being an indeterminate number of quantum particles? When they travel at lightspeed, time stops for them. I can tell this is to your liking. You’re frightened by your death too. By which road did you come to this place?

Oh dear. Here, put on my cloak. It’s not fashionable, but you’ll be glad for the armour. Many audience members are so troubled by the quantum particles they become violent. I trust you have a more humble perspective on your own significance. These particles, driven by probability, appear at strategic moments in a girl’s life and guide her towards discovering the tiny crumpled dimensions hidden within the four she must live in because of her size. You could use this skeleton and revisit your own life to see what could have been. At one point you’ll find yourself out beyond Andromeda. It’s really very pleasant there at this time of year. None of these? A shame, but I’m sure you’re certain which road to take next. Then, I have a woman who encounters a crow. His wing has been damaged by parasites, she believes. This woman knows about parasites. Her boyfriend is a comedian who uses her family tragedies as material. In this corrupt world, there are parasitic wasps that have their own parasitic wasps that have their own parasitic wasps, to the order of five, at which point reason breaks down.

It occurs to me that I, too, am being eaten from the inside. Do you think such a thing is possible?

Ha, ha, yes! In the hat and the cloak you are indeed halfway to becoming me.

There are many parasites of the body, and I do believe there are specialists for memory, frustration and shame. Nothing can be preserved in its original form. Everything is food for creatures that transform themselves. ‘Is this the world gone horribly wrong,’ asks the woman in the crow story, ‘or is it in perfect harmony?’

Exterminate the stories? Yes, I’ve tried several methods. Most recently by using one of these machines. It began harmlessly enough. I was even a little thrilled at the possibilities. But soon my body realised it wasn’t needed for the operation and disconnected itself, slumping into dull flesh. The intangible parts of me took flight.

Divorced from my body, the intangibles multiplied without limit. My people don’t connect with each other as they used to. Being insubstantial, they don’t want to be confined to the sounds of my damaged voice. As I operated the machine in good faith, they sensed eternity and converted themselves into energy. I’ve projected myself into the multiverse and my pieces will never return. And yet I find myself here, with you, friend, composed of something I can’t explain. But I’ve had enough now, my guts are gnawing at me. I just want a last meal of cutlets and an infinite sleep.

But damn this police chief, he won’t let me rest. He wakes me in the night to justify deeds he knows full well are wrong. For some reason he wants me to tell you more about him. Did he not do enough damage the first time I met him? I was only a simple vagrant when I found my when I found my way to his city. They didn’t need my stories there. The city was congested with tales already. He’s very troublesome indeed. Why should the jailer want his prisoner to understand him? Why should I try to understand?

No, no, don’t go. Let me detain you a little longer.

Through his work as the police chief of Odesa I absorbed many stories. I don’t know how long I can keep them all at bay. Those men, women and children he sent on the march to Siberia! He took time from their lives and used it to fortify himself. The police chief is not the only one who did this. All my people contain histories, which were laid inside them before they were born, just as they deposit their potential inside others, in a continuous chain of eating and being eaten alive.

I never sought to extend my own life. I hoped only to expand myself from the inside. Populate myself with people and places and impossible creatures so as to compensate for my meagre origins, and live a thousand thousand lives.

Yes, yes, of course these stories have endings. But the larvae have eaten them.

To know the endings you’ll have to take on the stories yourself. I think I will have that drink now, if you don’t mind. Somehow I have to stop treating the problem with more of the same. But when you’ve been become flint and walked out of your time, is there any way to stop? The stories have succumbed to the vanity of every species. They want to live purely to continue themselves.

I’m due to go to sea now, to observe the transit of Venus so that eighteenth-century navigators may better calculate their longitude. But the people on this ship are so consumed with fear and desire that none of us will ever return. The games they play evolve without rest and will coalesce into catastrophe. They don’t want to hear that I am held together only by a tremulous membrane. I’d hoped to return to my village soon, though I know it no longer exists.

Perhaps it’s time to let myself rupture, or I’ll never escape this jailer who wants the forgiveness I will always deny him. The membrane is straining to contain the parasites I’ve dreamed into existence. But tell me about yourself. I’ve been talking so much, I’m sorry. It’s your turn to speak now. I’m afraid I haven’t been entirely honest with you. The hat and cloak you’re wearing are infested.

…You don’t look surprised.

Who sent you?

Give them back then. I won’t hand them over if that’s what you’re going to do.

I’ve told you who I am.

He’s lying. Why would you believe a vagrant storyteller? Of course I didn’t try to kill him.

How could any man survive his throat being cut?

No, of course I’m not the police chief. Why would I murder a man I myself had sent to the camps?

What guilt? What shame?

Try to kill me then. See what good it will do your secret establishment. Have you not noticed that quiet person over your shoulder, absorbing every word we say?

No, you won’t catch them if you look directly.

Because they haven’t yet decided whether to take your place or not.

It doesn’t. My larvae have hatched and flown, they’re already burrowing into their new host.