Insubstantial Pageant

The world had died while she slept under the palm shelter. She’d killed it with the shock of her pact. Mountains had exploded and released glaciers that crashed into the sea. Oceans claimed the low lands while the orange dunes beneath her had buried the towers of steel and concrete. She’d woken into the corroded far future.

The world had had its fill of the diggers and builders; they couldn’t be trusted and must be returned to their constituent parts for the experiment to begin anew. Certain mistakes would not be repeated – opposable thumbs were forbidden the next time around so they couldn’t be misused to indicate that everything was all right when it wasn’t.

Almost everything under the shelter of dry palm leaves was as it had been when she’d fallen asleep: striped textiles and cushions on straw mats; date stones with flesh still attached; crushed plastic bottles and cups. But the men and camels had gone. She was stranded on this woven island under the meridian sun.

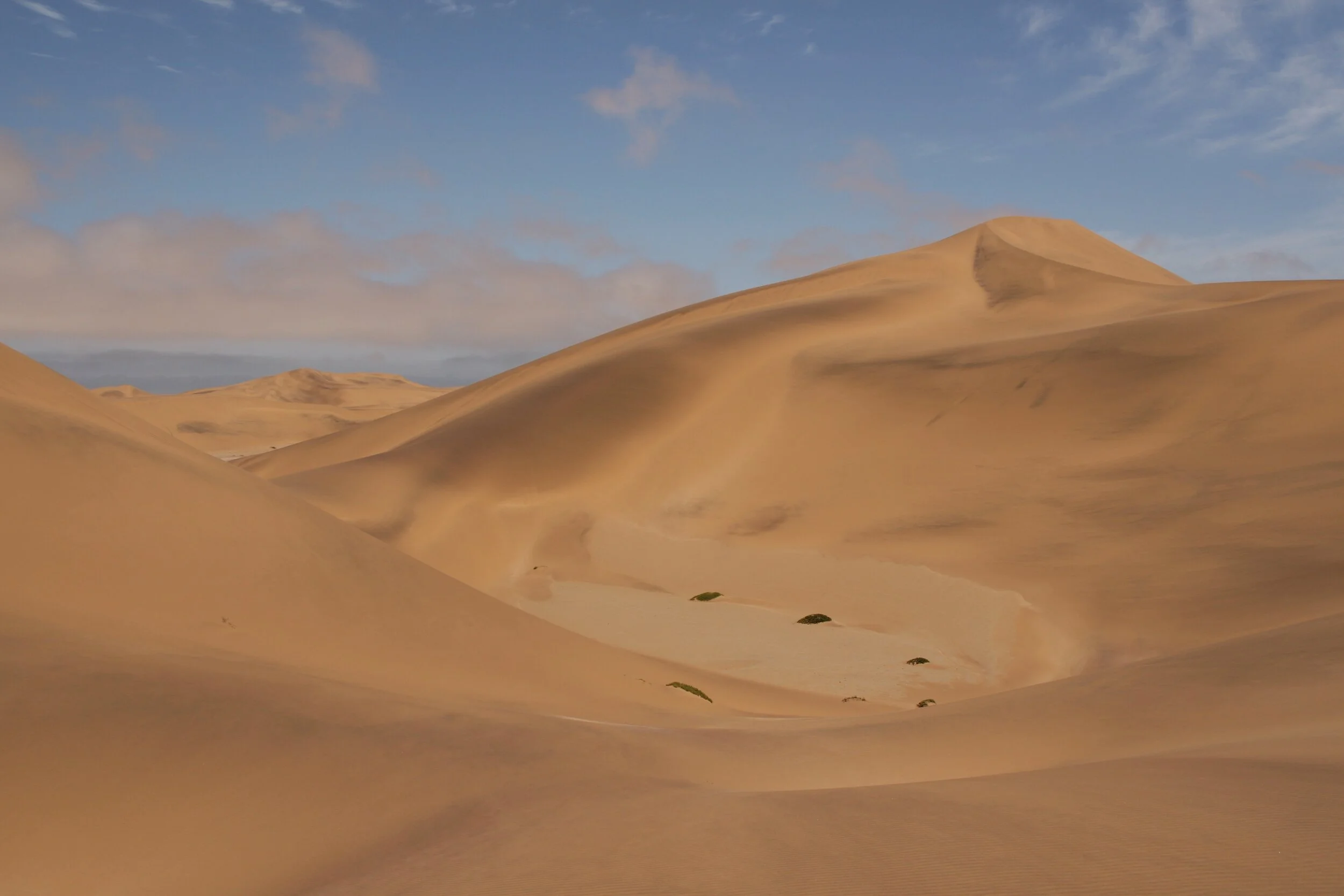

The sky was a featureless desert, indifferent to the orange sea that had advanced over the centuries as the wind bore grains up, up to the peaks, for gravity to roll them down the other side. She had the feeling of being upside down, of falling toward the blue wastes, accelerating at the speed of gravity so that she felt no friction. Most frightening was her relief.

But what was that ringing sound? She was deafened by a siren screeching from the rocks, yet neither the blue nor the orange sea had a shore. And that which could be lured to wreck itself was already here. She’d made a bargain in her dream. She agreed to pay an unnamed price, if only she need not return to the insubstantial city, where she designed tunnels that connected towers to utilities – tunnels through the sand upon which the city was rising.

The ringing, screaming sound took hold of her. It was the sound of her cells vibrating, her signature rhythm: she was a bomb that had just passed overhead. No, it was the memory of the bomb that had landed millennia ago, as preserved by the sand. The dunes, swept into crescents by the wind, sang of their own birth from the ashes of the known world.

There was no one but her in this new world, nothing to assist her continuance but this palm shelter and three soft black dates in a bowl. How did she know she herself was anything but dust? Her hand was a desert illusion, conjured by a parched mind. The screaming sound was holding her grains together and she should not want it to stop or she would collapse into formlessness.

It was impossible that she had a solid form. Therefore, she could not be blamed for building a city that would advance deserts across the nations that had missed their turn to be rich.

Why was she helping this process along? Because her education had prepared her for it. Because she was remunerated by sovereign wealth that flowed from extraction. Ancient lives ought to remain buried for the sake of the future ones, but without their resurrection the sovereign funds could not buy up the premium property in her home city. Why should latecomers not be allowed to buy their way into soft power as rich nations had done since time immemorial? Growth had to grow itself somehow. The only way she could absolve herself was to make a pact with the djinn in her dream.

‘I’ll pay any price to be free,’ she’d said.

‘Are you sure about this?’ said the djinn. ‘Events and inventions have been converging for centuries, your part is insignificant.’

‘It’s consequential to me.’

‘Not necessarily. Only when you know the future can you accurately explain the past that led to it. It’s quantum. Particles are entangled across space and time.’

‘Then I’m entangled with everything! Is this what the ancients called fate? If I can’t change other people’s decisions and acts, I was doomed before I was born.’

‘Don’t worry, Time will be reprimanded for the experiment with the thumbs,’ said the djinn. ‘She might even be replaced. Probably with another expat, you know how it is, who’ll impose their systems ready-made on a city in which the drivers aren’t familiar with the principles of roundabouts.’

‘I know someone who died on Television Roundabout,’ she said. ‘Even so, in a thousand years will today’s systems and science be thought of as anything other than whimsical myth?’

‘You’re all deluded in your relentless pursuit of knowledge. Physical laws of nature are only models of the world – you and the other thumbs have mistaken the model for the thing in itself.’

‘Then what am I seeing now?’

‘It’s spacetime in its true state,’ said the djinn. ‘You’re rather clumsy in that form, it’s a shame for us all that you can only apprehend one slice at a time. Spacetime is made of grains. They’re a dynamic player, quite mischievous really, you ought to watch your pockets should they bump into you and curve in response to your matter.’

‘But I’m such a small clump of atoms–’

‘And yet one day the clumps will bend spacetime,’ said the djinn, ‘and bring evolution full circle. Everything will happen and has already happened, it matters what you do with your atoms.’

The quality of the ringing changed. A shift in the frequency, or had something interrupted the waves?

The men returned with the camels and told her to drink. She was not completely alone with her pact. Tomorrow she’d leave the desert camp to fly back to the city on the thumb of Arabia, then she’d quit.

First she went to the coast. She faced the indivisible waves and emptied orange sand out of her pockets onto the grains of eroded coral. Broken shapes littered the shoreline. She gathered a few relics while they still had form.

*